I may be missing my audience with this post. I don’t have much hope many people will care about the later lives of two dead opponents of civil rights. But the stories of these two men are both not only fascinating to me as a microchasm of American race relations, but also inspire me to hope that people, myself included, can change. So, here’s an introduction to Governor George Wallace and Senator Robert Byrd in the 1960s.

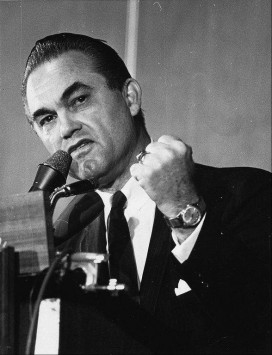

George Wallace: Champion of Segregation

George Wallace came from a political family and was active in politics from a young age. At age 33, he was an Alabama Circuit Judge and issued an injunction against the federally-ordered removal of segregation signs from train stations. By 1962, he was elected Governor of Alabama. In his inaugural speech he used the line which often defines him:

In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.

In 1963, after integration of Alabama schools was ordered by a federal court judge to admit black students to the University of Alabama. Three students–Vivian Malone Jones, Dave McGlathery and James Hood— were admitted, but as Jones and Hood arrived to register, Governor Wallace personally blocked their entrance to Foster Auditorium, where registration took place. After federalizing the Alabama National Guard, John F. Kennedy ordered Wallace to step aside. After some bluster, he did.

Robert Byrd: Exalted Cyclops?

Robert Byrd’s first leadership roles were in the chapter of the Ku Klux Klan in his home town of Sophia, West Virginia. He eventually became the top official in the chapter (Exalted Cyclops). In 1946, at age 28, he wrote this gem to segregationist Senator Theodore Bilbo:

I shall never fight in the armed forces with a negro by my side … Rather I should die a thousand times, and see Old Glory trampled in the dirt never to rise again, than to see this beloved land of ours become degraded by race mongrels, a throwback to the blackest specimen from the wilds.

In 1964, he joined other Democratic Senators in a filibuster of the Civil Rights Act.

Into every life…

By 1972, George Wallace had been elected Alabama governor twice and completed an unsuccessful 3rd party bid for President in 1968. While campaigning in a bid for President, he was shot 5 times. One bullet hit his spine, leaving him paralyzed from the waist down. He would remain so for the rest of his life.

Robert Byrd, by his own account, experienced a crisis of faith in 1982 when his teen-aged grandson was killed in a traffic accident.

For both men, life taught them some things they didn’t know in their twenties and thirties. Byrd recalled that his experience with losing a grandson brought him to the realization that “African-Americans love their children, too.” Wallace describes being “born again” some time after his attempted assassination.

For both men, this new wisdom translated into markedly different public policy. For most of his later career, Senator Byrd’s voting record was dubbed perfect by the NAACP. In Wallace’s last term as governor, he made a record-setting number of appointments of Black men and women to state posts. Both men made concerted efforts both to distance themselves from racist groups, to encourage others to avoid their mistakes, and to make clear their remorse at their role in the oppression of Blacks. Wallace attended the 30th anniversary of the Selma-to-Montgomery march, addressing the crowd and asking their forgiveness. “May your message be heard,” he said. “May your lessons never be forgotten. May our history be always remembered.” How it must have pained Wallace to think of his name forever associated with bigotry and racial violence.

Skepticism?

I sympathize with those who might express skepticism with this change of heart for both men. They each continued to make decisions which continued to reveal hints of racism or at least racial ignorance. It’s certainly possible that they’re simple opportunists whose views changed with public opinion. But Wallace and Byrd are both men who demonstrated their ability to take a bold stand against the popular tide. Byrd was the Senate’s staunchest opponent of the Iraq War. At the height of American anger and fear, he exhorted toward calm and care. Both have been outspoken advocates for progressive racial policies to audiences who did not welcome the message.

It would be a shame to let the behavior of these 30-somethings dictate our view of them for the rest of their lives. A nation that takes such pride in its Christian foundations, should rejoice at these stories of redemption and should emulate the example, especially of Governor Wallace, in admitting and seeking to rectify our mistakes at both a personal and a national level.