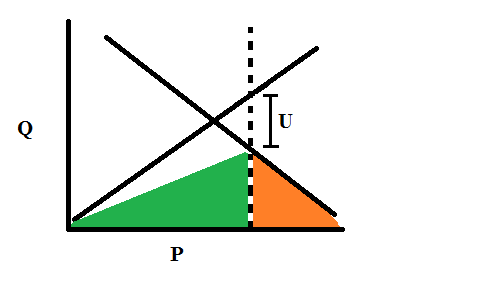

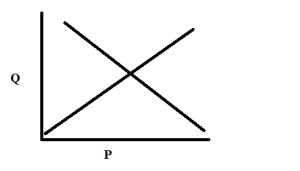

There are no economists at ThisWeekInStupid. But, that’s not going to stop us from weighing in any more than it stops economic ignoramuses like Paul Ryan, Bernie Sanders or Peter Schiff. Recently, we penned a piece opposing a minimum wage hike, or at least suggesting that there were plenty of other ways to help minimum wage workers that were less apt to cause unemployment. Today, we’re going to go back on that a little. The main argument against a minimum wage involves, naturally, a supply and demand plot, like this one.

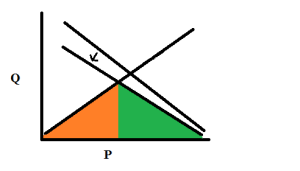

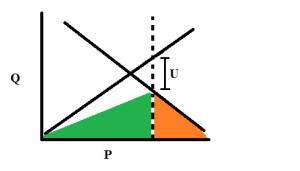

The downward sloping curve is the demand for workers. These are the employers who hire fewer workers when the wage is high. Many businesses can make money hiring workers for $4/hour. Fewer businesses can operate profitably paying $15/hour and very few can survive if they must pay $25/hour. The other curve, which slopes upward, is the supply curve. These are the workers. For $4/hour, lots of people will go back to school or live on their spouses income or live in their parents’ basement rather than work. For $15/hour many more will be willing to work. And for $25/hour, workers will come out of the woodwork. They’ll get childcare, come out of retirement, rearrange their class schedule, etc. (Note that this curve assumes all workers are equal, which is nonsense, but it may be illustrative anyway.) Where these two curves meet is the equilibrium wage. That’s where wages will naturally fall without any government interference. This next graph is decorated a little more.

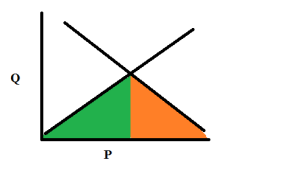

In this graph, I’ve colored two regions underneath the curves. The green region represents the producers surplus–extra profit for workers. That is, there are some workers which would have been willing to work for $4/hour. They consider their hour to be worth $4. If the equilibrium wage is $6/hour, then they are $2 richer for every hour they work.

The orange area is the consumer surplus–extra profit for employers. Some employers could break even by paying workers $8/hour. If they only pay $6/hour, the employer is wealthier by $2 for every hour worked. These two areas are what make capitalism fun. Voluntary exchanges make both parties wealthier. Always. So is it ever a good idea for government to interfere with voluntary exchange? Let’s see.

The effects of a minimum wage

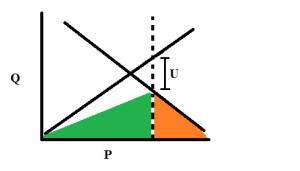

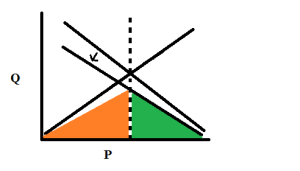

When a minimum wage is introduced above the equilibrium wage, a few things change. The first result is unemployment. In our curve, the equilibrium wage might be $6/hour. With a minimum wage set at $8/hour, two things happen. First, more people are seeking work. Second, fewer businesses are willing to hire. Both of these effects cause unemployment (but only the second of these effects represents a change in employment from the equilibrium situation). It’s represented by U in the plot below.

At the new wage, employers are demanding fewer workers than the total workers seeking a job. Liberals should stop denying this effect. It’s true that there are studies that found that in a subset of businesses hiring minimum wage workers, the effect on employment was weak or absent. But these studies and others also point to a stimulative effect of a minimum wage wherein wealth is transferred to poorer workers who tend to immediately spend their money. This tends to boost demand. So the question is, if there’s a boost in demand, why does employment stay the same? Why doesn’t it increase? A natural explanation is the argument above. The first order effect is the one we see on the supply and demand curve pushing employment down. The stimulative effect helps to mitigate that effect. Also, there are many careful studies which reach the conclusion that a minimum wage does decrease employment.

Returning to the supply/demand plot, let’s look at what’s happened to the green and orange regions. The wage is higher, so the green region would be the area under the supply curve up to the new minimum wage. Except that there is unemployment. Only a fraction of the workers desiring employment can find jobs. So we should reduce the green region by the unemployment. An approximation of that is the green shaded region above.

The orange region is more straightforward. Those employers who could not profit by hiring workers at the minimum wage, stopped hiring. So the orange region is the area under the demand curve above the minimum wage.

So, are the workers, collectively, better off? Certainly those workers who keep their jobs are better off. Our worker who was willing to work for $4/hour is now making $8/hour and gaining wealth at $4 for every hour worked (up from $2 before the minimum wage). But, some other workers, including some willing to work for $4/hour, have lost the chance to work. In many cases, this represents an overall gain for the workers as a whole. It’s easy to see how the new green region could be larger than the old especially if the demand is quite inelastic–that is, if demand for workers stays largely the same as wages increase. But when this is the case, it’s important to ask, where did this extra money come from?

Partly, it comes out of the profits formerly collected by the employers. In our new curve, the orange region is clearly smaller. Employers of minimum wage workers will almost always argue against a minimum wage. The first order effect is to shrink their profits.

Another source of increased wages for workers is increased prices for the end goods. Conservatives often say dumb things like, “Employers just pass the additional costs on to consumers.” This is lazy economics (just ask a non-economist!). There’s a separate supply/demand curve for whatever good or service the employer is selling. Presumably, this curve is what set the consumer price of the end good in the first place. Unless the minimum wage changes the market for end goods, the pricing strategy of the employer is unlikely to change much. Of course, the supply curve for the end goods may change as competitors with smaller profit margins who cannot afford the new higher wage, drop out of the market. This may cause prices to rise, but it will still be subject to the end consumer demand curve. Consumers will not blithely pay higher prices just because our employers’ costs rise. Research shows that something like one-third of the additional cost of a minimum wage hike is passed to consumers as higher consumer prices.

So, some of the extra worker profit comes out of employer profit and some comes from the end consumers. One important thing should be clear from the plots. The profit the workers gain from the minimum wage is always less than the profit the employers lose. That is, the first order effect of government interference is to reduce the overall wealth of the economy. This should have been obvious from the beginning. When a worker valuing his time at $4/hour works for an employer who values that same work at $10/hour, there is, in total $6/hour profit to be made and split between the employer and employee. Changing the wage shifts the allocation between the employer and employee, but does not affect that total. So the total possible surplus (consumer + producer) was fixed before the minimum wage was introduced. The minimum wage can only affect this total by prohibiting some of the exchanges, reducing the total profit.

So, isn’t a minimum wage just a terrible idea?

Redemption?

Not necessarily. Think of a minimum wage as a leaky pipeline that transfers wealth from wealthy employers to less wealthy workers. There are some good reasons to redistribute wealth downward. First, wealth exhibits a diminishing marginal utility. That is, each dollar improves the life of a poor person more than it does a rich person. To a poor person, $500 may mean repairing his only car or fixing his children’s teeth. Meanwhile, to a rich person, it may mean an additional Coach purse or a spectacular bottle of wine. Even though the total amount of stuff has not increased (and has, in fact, decreased) the utility of the stuff, or the happiness it produces, may increase.

The second reason to redistribute wealth applies only in a Keynesian recession. When an economy is in the doldrums due to deflation and weak demand, shifting wealth from rich to poor can boost the economy since poor people tend to spend their money more quickly and readily than rich people. This moves money through the economy faster and creates inflation. In an economy dogged by deflation due to a shrinking money supply and weak demand, this is a welcome effect. But, in an economy operating at full capacity or one experiencing supply-push inflation, this is a problem. More spending can cause inflation to run too high, distorting price signals. The great part about a fixed minimum wage is that inflation quickly makes the minimum wage irrelevant as wages are pushed above the mandated minimum. A minimum wage below the equilibrium wage is like having no minimum at all. So a mildly restrictive minimum wage is an automatic recession fighter providing stimulus when demand (and wages) fall without causing inflation when wages rise.

Rent-seeking

The final reason to redistribute wealth, especially through a minimum wage, comes from Henry George (whom modern economists ignore at their peril). George and his disciples point out that at least some of the profits employers collect are “economic rent” on the non-produced inputs to production. That is, the division between employer and employee may be partly because of something about the employer which does not make her more productive. Certain people may have better access to capital due to their birth or connections or physical characteristics or land ownership or habitus. Where these characteristics are unrelated to productivity, they amount to a contrived exclusivity, depressing the demand for workers and reducing wages. Marx would say that the separation of the workers from the means of production enables excessive profit-taking by employers. Of course, not all advantages of employers are rent taking. An employer who has labored to produce 10 shovels might reasonably hire 10 workers to use them, taking profit for providing the shovels. But, when that employer takes additional rent because she owns the land or because her father-in-law fronted her the money for the shovels or because she has an exclusive right to produce or use shovels, she’s collecting economic rent. Rent-taking reduces the efficiency of markets and destroys wealth in the same way a minimum wage does but to the disadvantage of workers. A minimum wage forbids any exchange of labor for money below a certain wage. Rent requirements forbid or discourage businesses started by otherwise productive people without the right characteristics or connections.

A brief clarification is probably a good idea here. In economic terms “rent” is not only the money you pay your landlord to continue to live in your apartment (although that’s one example). It’s also the benefit you get from being white or being the boss’s nephew or even for holding the patent on a product. Not all assets on which you collect rent are nefarious or unfair. But what makes it rent-taking is that you benefit for some other reason than that you’re more productive.

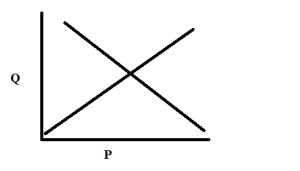

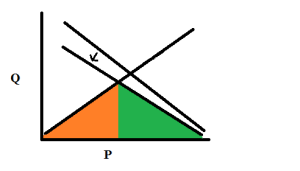

Let’s look at our supply and demand curves again. Rent requirements artificially reduce the number of potential employers. For simplicity, we represent this as a simple multiplicative reduction in the labor demand. Suppose that our rent requirement means that 15% of potential employers are pushed out of the market.

In the curve above, it’s clear that the downward shift in demand reduces the wage and increases the profits for the remaining employers. At the same time, the employment shrinks. The effect is, in fact, quite similar to the effect of a minimum wage with the increased profits for employers coming partly from decreased profits for workers.

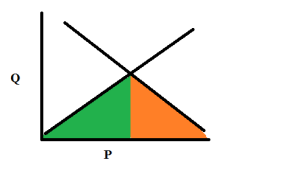

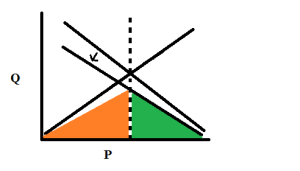

In cases where there are rent requirements for new businesses, a minimum wage may boost wages which were artificially suppressed by rent-seekers. But, a minimum wage is a very blunt instrument. It harms both rent-seekers and naturally profitable businesses. In this curve, we can see that the combination of a minimum wage and rent requirements is better for workers than no minimum wage (or might be), but still much inferior to eliminating both the minimum wage and rent requirements.

Here, the minimum wage has pushed the price back out to the equilibrium price, but it cannot undo the effect of the rent requirements. An economy is much better served by finding ways to reduce rent-seeking, especially since both the minimum wage and the rent requirements drive up consumer prices. But, in markets dominated by rent requirements, a reasonable minimum wage may do more good than harm.